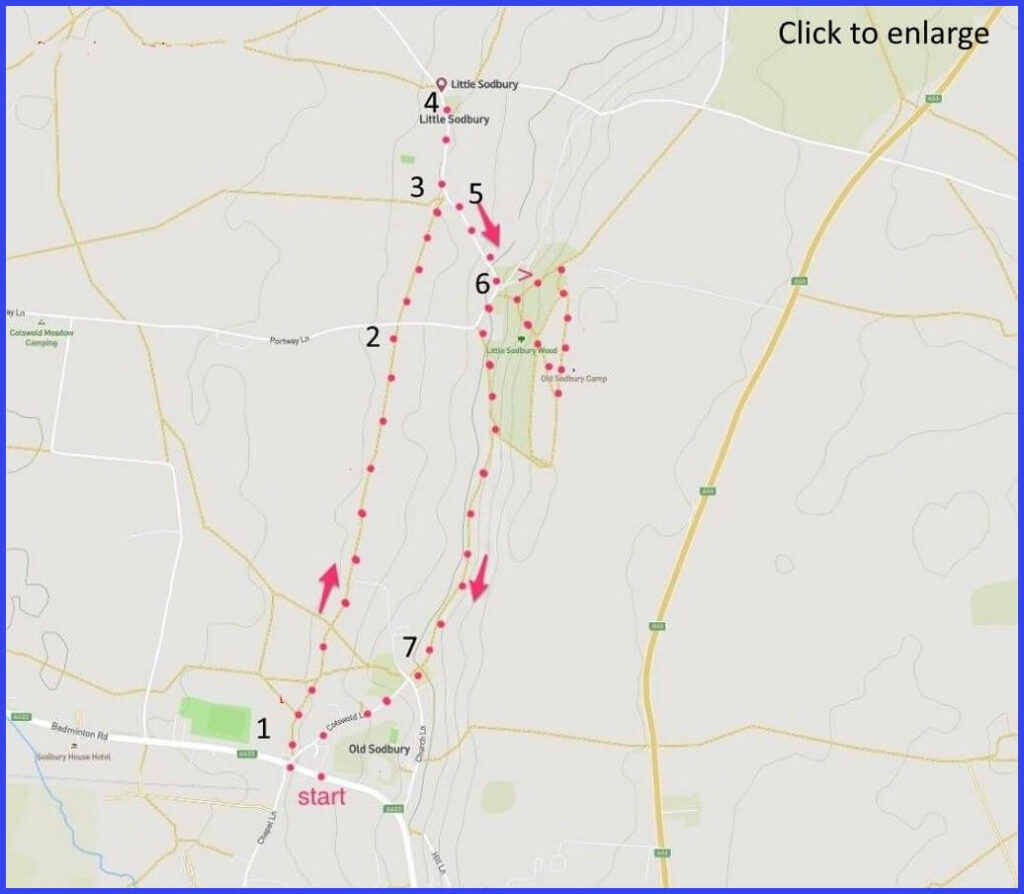

BS37 6LZ A 4-mile walk around Old Sodbury with some steep parts, no challenging crossings. Park near the pub. Head up the Cotswold Way, reverse, see the fort, and the churches. Click map to enlarge. Water is blue, wooded green, contour lines show slopes. Click here for an aerial view Click here to download/print PDF. (There is a GPX route option here for phone/tablet download. But only follow this link after watching this GPX help video). Friendly warning: all files relating to walks are published here on good faith but on the understanding that users must be responsible for their own safety and wellbeing.

Start Cross the main road to ’20’ road sign at Cotswold Lane. 20m

1 Quickly veering left off Cotswolds lane to join a footpath through farm buildings that is the Cotswolds Way. A gate on right opens a diagonal path across field towards a kissing gate. Then simply follow the line of overhead cables (pic A & B) through fields/gates until you reach Potway Lane crossing your path. 1.2km

2 There is an access gate under a pylon. Cross to a gate opposite. Take path to right of line of trees and follow rightwards towards the far corner of this field. 340m

3 Gate in far right corner opensto lane (pic C). Left turn and walk towards church [E]. 260m

4 Retrace your steps passing that gate again on your left to uphill climb (pic H)on the lane. 310m

5 Stay on this lane until reaching a Y-junction. 240m

6 Here you may improvise your inspection of the hill fort (pic I) which appears after a climb. Trace a path back to the lane at point 6. Continue down to the junction with Portway Lane. At this sharp right bend, pick up the footpath on your left instead and rise up this and onward back towards Church Lane in Old Sodbury. 1km

7 The footpath leads into Church Lane (visit Church? [J]) but follow Cotswold lane downhill to your starting point. 400m

The pictures below are in the order things were seen on this walk. Clicking on any one will enlarge it (and the slideshow)

The walk

Parking is possible near the point where this route is anchored in ‘Old Sodbury’, namely the Dog inn (good for refreshment, albeit on a busy road). It then traces the Cotswold Way (a long National Trail that follows the escarpment of the Cotswold Edge) to a still smaller Sodbury, engages with a great Englishman, and finally offers exploration of a large iron age hill fort (“Sodbury Camp”) around which the three Sodburys lie (Chipping, Old and Little).

William Tyndale lived here

Little Sodbury is one of England’s ‘Thankful’ villages because all Great War recruits from here returned safely (surely joining this club is easier for a small village?). The suggested destination is St Adeline’s church (pic E & G) – once a medieval chapel to the manor house but then, after deterioration, replaced in 1859 by a close copy. The village is known for its association with William Tyndale (1494-1536). That original St Adeline chapel doubtless hosted him as a preacher (pic F). Tyndale’s fame follows from his status as the “most dangerous man in Tudor England” (Melvyn Bragg). Little Sodbury’s own fame follows from his time as chaplain and tutor to Sir John Walsh’s children at Little Sodbury Manor (1521-23).

Tyndale’s ‘dangerous’ status arose from his translating the Bible into English, aiming to “cause a boy that driveth the plough to know more scripture than the clergy of the day“. Meaning that folk such as those driving a plough in the fields of Little Sodbury could access scripture independently of the church and its clergy. His wasn’t quite the first translation project but its fluency and its authoritative grounding in Hebrew and Greek sources ensured it was more influential than the 14th century translations of Wycliffe. It certainly didn’t enjoy catholic church approval. Indeed some of his provocative translations (‘church’=’congregation’ and ‘priests’=’elders’, for example) positioned him as a threatening source of emerging non-conformist Protestantism.

Although Tyndale wisely fled the country to finish the task (published 1526), his efforts were formally condemned, banned, and burned in England. In 1536 he was betrayed and defrocked, ultimately being strangled to death and burned at the stake. Tyndale probably only made matters worse by declaring his opposition to Henry VIII’s divorce. Although Anne Boleyn did share with her husband Tyndale’s book “The Obedience of a Christian Man” in which it was asserted that kings were accountable to God, not the Pope. This may have spurred Henry on towards announcing his role as head of the Church in England. Therefore, indirectly and ironically, Tyndale ended up laying significant protestant foundations in the Green and Pleasant Land.

The manor house where Tyndale started this subversive business still thrives. Sadly, it is in private hands and so not open for inspection (last sold for £7.8m). However, there is a surveyor’s flythrough that gives some idea of its scale. Why is Tyndale worth this attention when there is now so little visible sign of him here? It depends how you reflect on such things. Put simply, it might stir something in a walker to momentarily share a space with someone who had such a profound political and cultural impact on the practice of Christianity. And who, via his translation, contributed a whole raft of now so-familiar words and phrases to the English language.

Fort and church

The hillfort is one of the finest (largest) examples of a Bronze/Iron age encampment – certainly in the Cotswolds. Its double set of ditches suggest a well-chosen secure place. The area is now private property and so it is important to respect the official footpaths. Coins that have been found indicate that the area was also utilised by the Romans. Its panoramic security may have encouraged Edward IV to camp there in 1471 prior to the Battle of Tewkesbury. This lofty and protected height means that – on a good day – you can see perhaps as far as Wales. A good sense of scale is revealed in this drone video (helpful, despite irritating drone-y music)

On reaching the main road again it is worth taking a look at St John’s church (pic 10). The churchyard is often more occupied than the building, because its wall offers a splendid view across the Severn and towards the Welsh mountains. At which point, a visit to the Dog Inn might feel quite timely and deserved.

![[A]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/01sod-150x150.jpg)

![[B]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/02sod-150x150.jpg)

![[C]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/03sod-150x150.jpg)

![[D]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/04sod-150x150.jpg)

![[E]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/05sod-150x150.jpg)

![[F]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/06sod-150x150.jpg)

![[G]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/07sod-150x150.jpg)

![[H]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/08sod-150x150.jpg)

![[I]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/09sod-150x150.jpg)

![[J]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/10sod-150x150.jpg)