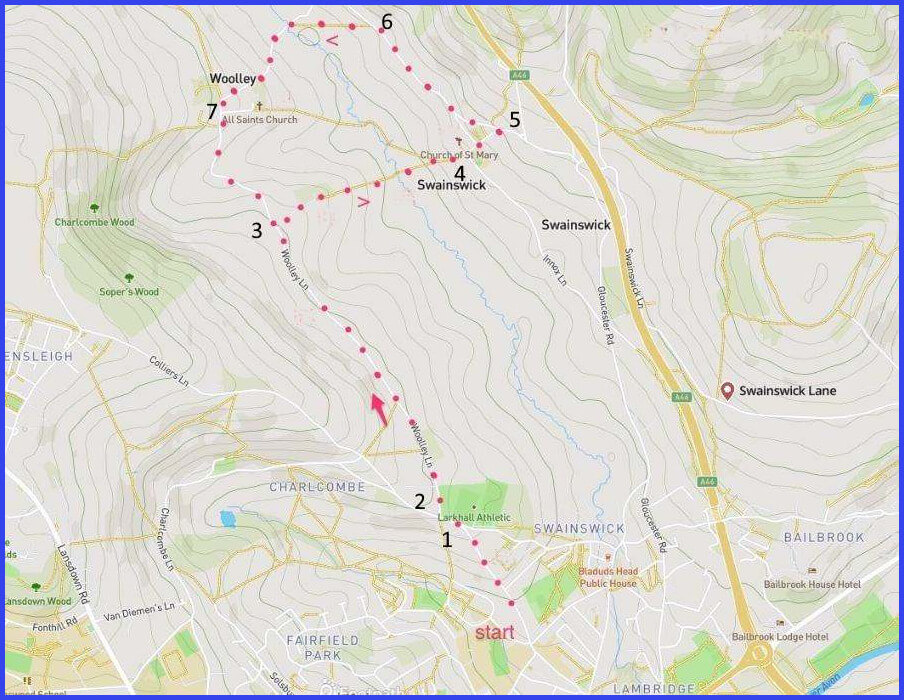

2 Walk forward [D] with undulating country [C] on your right. 1.2km

4 Climb a few steps into what looks like someone’s garden but which opens onto a left turn that leads to the Swainswick church (pic H). Visit. Return to junction and walk upwards to Tadwick lane where the lane turns left. 200m

5 Walk forward on Tadwick Lane passing Manor House until a marked footpath appears on your left. 400m

6 Take this footpath diagonally across field to join ‘High Street’ that heads down, shortly veering leftwards, into Wooley village. 400m

7 Detour left to see the church [J]. Return to High Street which then turns into Wooley Lane, taking you back to Larkhall shortly retracing your steps. 2.4km

The pictures below are in the order things were seen on this walk. Clicking on any one will enlarge it (and the slideshow)

The walk

Parking is easy in some part of Larkhall village that is near the marked start point for the guide here. This route lies on both sides the Swainswick valley. Departing from Larkhall, a steep residential incline meanders past the football ground of Larkhall Athletic (“The Larks”, Southern League Division One South, still fighting).

After veering right (onto Woolley Lane), a long section offers attractive views of the valley to the right. This whole area is designated a ‘Site of Nature Conservation Interest’ – unsurprisingly, its often painted and photographed (pics B & C). Historically, most of it has been agricultural, although there is some evidence of milling on the river. Crossing the valley by field paths leads you up to the village of Upper Swainswick on the other side. The route then goes across to the second village – Wooley from which a lane leads back to re-visit the early part of this route. Nothing about this route is difficult, although the walk across the valley is, naturally, an up and down journey that is a little steep.

Upper Swainswick

The valley at the start of this walk is elsewhere described as the valley of the Lam Brook, a river which ultimately joins the Avon (just beyond the A4 at the Bath Rugby training ground). As is often the case, it is the journey of a river that defines the pattern of human settlement. Of the five villages around the valley, the walk described here will take in two of them. Both comprise mostly 17th century buildings (or earlier) and both offer some interesting history.

Although small, Upper Swainswick has appealing features (the local MP not being one of them). In particular, there is St Mary’s church, part of a three-way local Benefice (with St Saviours Larkhall, and Woolley). This church seems very community-friendly. It organises a monthly village beer festival (Pub Swainswick – possibly discontinued), harbours a refreshment area for passers-by, a toilet (back of building), and agreeable scattered seating in the churchyard (pic I). It also boasts a group of active ringers who work its six bells. Take a guided video tour here (possibly the vicar?).

Buried at this church are John Wood the Elder (1704-54, Bath Georgian architect) and Thomas Prynne. The Prynne’s had lived long in this village; a family that included Thomas’ distinguished son William (1600-69). During the Civil War and Restoration period, the more famous William Prynne had been a vigorous Puritan pamphleteer (of the ‘no-to-Christmas’ variety). His evangelical vigour cost him dearly: a withdrawn Oxford degree, a period of imprisonment, the branding of his cheeks, and removal of both ears. Despite all this, albeit in later and more sympathetic times, he later became MP for Bath.

The Manor House – in which the Prynnes lived at various times – is visible to the left as when walking up Tadwick Lane, away from the village. The manor was sold in 1529 to Richard Dudley, a Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford (the house was recently on the market for £1.8m). Shortly after the sale, Dudley donated the whole estate to Oriel who administered it into the twentieth century. The connection with Oriel College recently re-surfaced around a demand from the mayor of Bath that the college return a ceremonial sword believed to properly belong to the village. A duel was proposed.

However, what Swainswick is best known for is the legend of Bladud. This is widely enough reported (in all its different versions), so only an outline is necessary here. Geoffrey of Monmouth started it with his ‘History’. Basically, the talented Prince Bladud had been banished on account of his unfortunate leprosy. He subsequently gathered a herd of pigs to eke out a living (around Swainswick). The pigs started rolling about in, a hot spring which lessed their skin conditions. Then it worked for Bladud’s leprosy. So Bladud founded Bath at the source of these springs (100 years before the Romans came) in order to take advantage of their potency.

A thankful village

A walk back across the valey leads to the Saxon village of Woolley. Here there were once two corn mills (now converted). However, its more famous industrial history concerns gunpowder. A works established in Bristol sought more discrete, country-based sites for production, ideally with water sources and plenty of wood for charcoal. Woolley was one choice in a small network. The works (established in 1722) were overseen by the Parkin family and managed in the village by the Worgans. It was a business closely involved with the slave trade – wherein gunpowder played a valuable bartering role. However, around the start of the nineteenth century the works began to wind down – partly reflecting the abolition of slave trading, but also the growth an a gunpowder industry in North America.

Elizabeth Parkin (Lady of the Manor) paid for building the church of All Saints in Woolley (1761). It replaced an earlier mediaeval structure and is notable for its bell tower and cupola (pic J). The design is by John Wood the Younger. If visiting this church, one thing that might attract attention is a plaque reading: “In thankful remembrance of the safe return of all the men Connected with this Parish who by land and sea served their King and Country In the Great War”. This ‘all out and all back’ good fortune makes Woolley one of 24 (so far identified) so-called ‘Thankful Villages’ who can claim this. Moreover, in addition to the 13 men who fought in World War I and safely returned, 15 did the same in World War II. This makes Woolley one of just 17 ‘Doubly Thankful Villages’. Let’s hope it never achieves the triple.

![[A]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/01wool-150x150.jpg)

![[B]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/02wool-150x150.jpg)

![[C]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/03wool-150x150.jpg)

![[D]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/04wool-150x150.jpg)

![[E]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/05wool-150x150.jpg)

![[F]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/07wool-150x150.jpg)

![[G]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/06wool-150x150.jpg)

![[H]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/08wool-150x150.jpg)

![[I]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/09wool-150x150.jpg)

![[J]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/10wool-150x150.jpg)