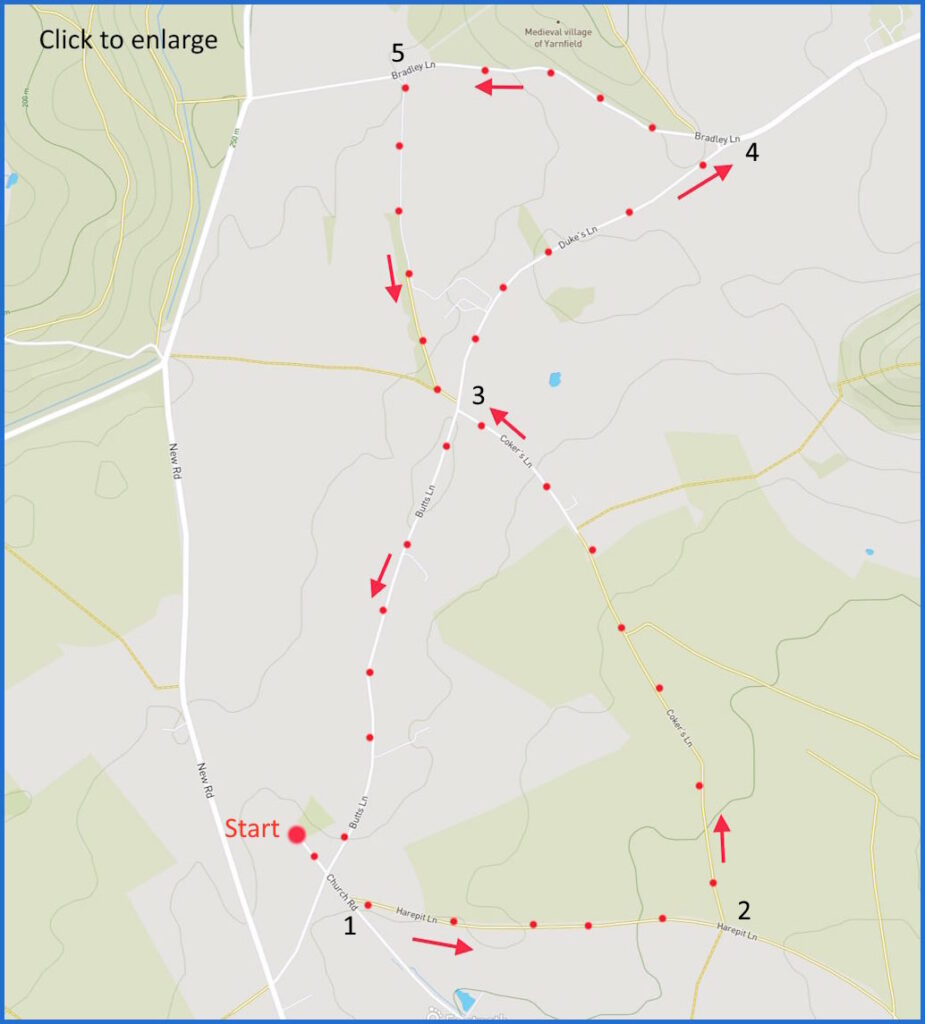

A 4-mile easy figure-of-8 walk around Kilmington. Click map to enlarge. Largely flat, all lanes, byways, some quiet country road. Arial view here. Click here to download/print PDF. (There is a GPX route option here for phone/tablet download. But only follow this link after watching this GPX help video). Friendly warning: all files relating to walks are published here on good faith but on the understanding that users must be responsible for their own safety and wellbeing.

(Routes from map points + metres to next point).

Start: From outside church, walk to end of Church Lane, cross intersection towards path junction on right 220m

1: To first junction to left (Coker’s Lane) 890m

2: Turn left, walking forward to 4-way intersection 1.4Km

3: Take lane heading right (see closeup here) 900m

4: Walk to first junction on left 890m

5: Walk forward to earlier junction (closeup) 900m

3: Return to start 1.3Km

The pictures below are in the order things were seen on this walk. Clicking on any one will enlarge it (and the slideshow)

The walk

A walk perhaps more precious for silence than scenery – but still rewarding. It is an easy, flat walk – no stiles, fields, copses, or restless cattle. Some of the byways are used by farm vehicles, so there may be a chance of some mud under foot if there has been much rain recently. The walk is shaped as a figure of 8 and so there are several ways to navigate it in addition to the one that happens to have been documented here. Some of the route is on roads used by vehicles. They are narrow in places although in two hours we only encountered seven of cars, and met them with no difficulty.

Historically, the area has been a largely agricultural community, although there was an attempt to introduce textile and malting work in the 19th century. At the same time a small silk industry was also started – connected with that at nearby Bruton. One remnant is visible in the village (but just off the southern portion of this walk) – namely the The Silk House at 69-74 Cote Lane. This silk workshop was converted into six small dwellings in 1849; finally to be purchased by the National Trust.

The source of the river Wylye is at Brachers Well from which it runs above ground intermittently through the village and appearing to the east.

There are three buildings on this route of special note. First there is St Mary’s church – where it is suggested you start this walk. It most likely will be locked although, if not, there is a fine stained glass east window to admire inside. There has been a church here since Norman times. But only the tower is medieval (15th century), while much of the body of the church has been rebuilt. There is a pleasant space surrounding it.

Second, and next to the church, is the attractive and rather rambling Manor House – once the ‘dairy house’. There is little sign of its 14th century origins but it has been pleasantly refashioned. The final settlement to note is one you pass on your way up Coker Lane. A set of industrial buildings on the right is signed for ‘Bruce Munro Studio’. This is the base of British ‘light artist’ Bruce Munro. See some examples of his work are here.

Kilmington and the Stourtons

The village is intimately linked to the nearby Stourhead Estate in the manor of Stourton – land which had been owned by the Stourton family since before the Norman conquest. The first Lord Stourton was created thanks to Henry VI in 1445. Successive lordships flourished until the 8th Baron, Charles – whose downfall is closely linked to Kilmington and its church.

This is how. In 1544 William, the seventh Lord Stourton (1505–1548), purchased the Manor of Kilmington from the Crown. On his death he left everything to his mistress Agnes Rhys. She promptly occupied Stourton House resisting the eviction efforts of the (now disinherited) son Charles – 8th Baron. Agnes was eventually put out of the manor, although she entered litigation against Charles – something that was not settled until after his death. But his death is the dreadful core of this Kilmington story.

Charles Stourton was a pretty disreputable man. But so was his nemesis, William Hartgill. Hartgill lived in Kilmington and was steward to Charles’ father William, the 7th Lord. He was also an MP – probably due to Lord Stourton’s influence.

Hartgill got on the wrong side of Charles by defending the 7th Lord’s will and at the same time prompting a series of disagreements over land ownership and livestock thefts. Charles organised his servants to hassle Hartgill and ultimately imprisoned him and his wife in the tower of the Kilmington church. However, Charles Stourton suffered a period in prison himself for this – and a requirement to pay damages. Doubtless causing even more Stourton anger. But Charles arranged that the damages would be paid and would do so at a meeting to take place between them in the church. But when Charles arrived with purses to pay his debts it was with 15 or so of his servants and a group of the local gentry.

Rather than pay the damages, Charles tricked the Hartgills into coming forward and then he arrested them on a false charge of felony. They were tied and imprisoned again. They were released following a visit from justices of the peace but Stourton’s servants re-captured them and clubbed them to death in a particularly brutal manner. It is probable that one of the servants betrayed Charles Stourton because the buried bodies were found and Stourton was arrested. He was indicted in Salisbury and then tried by his peers at Westminster. He was hanged. However the hanging was carried out with a silk rope to respect his nobility. This makes him only the second peer to be executed for an offence short of treason.

To complete the picture you might consider a visit to the nearby Stourhead estate

![[A]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kilmington_01-150x150.jpg)

![[B]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kilmington_03-150x150.jpg)

![[C]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kilmington_04-150x150.jpg)

![[D]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kilmington_02-150x150.jpg)

![[E]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kilmington_05-150x150.jpg)

![[F]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kilmington_06-150x150.jpg)

![[G]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kilmington_07-150x150.jpg)

![[H]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kilmington_08-150x150.jpg)

![[I]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kilmington_09-150x150.jpg)

![[J]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kilmington_10-150x150.jpg)