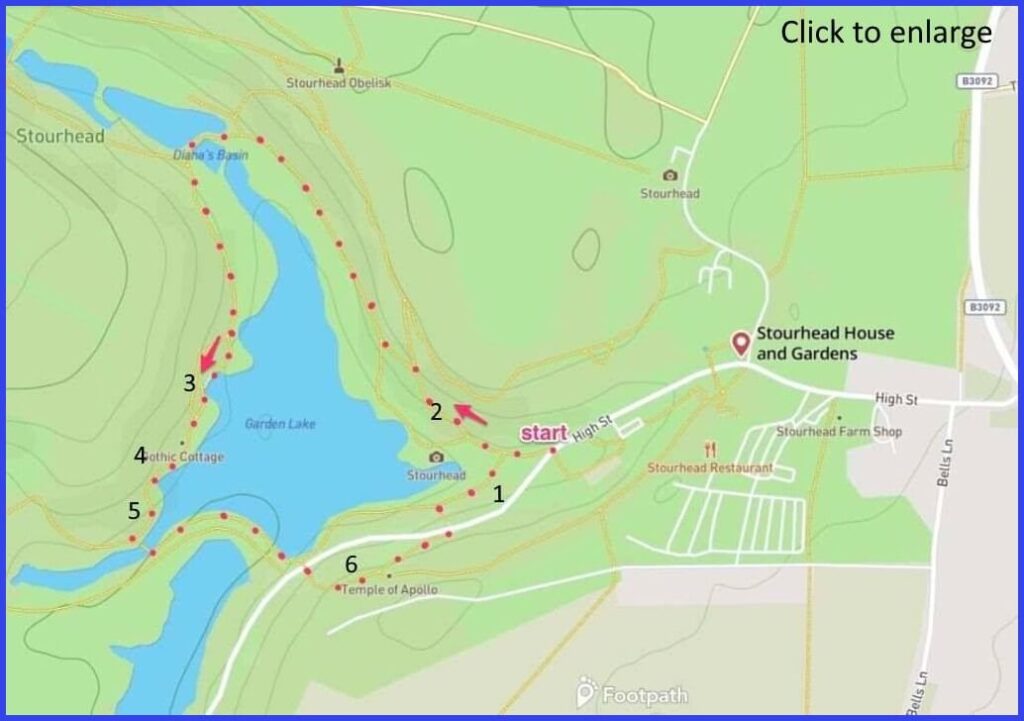

BA12 6QF An easy walk around Stourhead (with easy opportunities to extend). You can walk around this site for free (dogs requested to be on leads). Although if you are driving you may find it most convenient to use the National Trust car park. If you are not a member this will require a pay-and-display ticket to be purchased. (Click map to enlarge. Click here for an aerial view) Click here to download/print PDF). (There is a GPX route option here for phone/tablet download. But only follow this link after watching this GPX help video).

The path outlined in the picture is just one suggestion and seems transparent enough not to require a detailed textual description here. However, on this map (or on the official guide) you may notice other paths that you would lke to add that suitably enrich your visit. Observations below are only applying to the route shown

The pictures below are in the order things were seen on this walk. Clicking on any one will enlarge it (and the slideshow)

The walk

The National Trust has a car park for Stourhead. There may be other places to park and they may save you paying but the official car park is probably the easiest place to start. The route is simply that which most people will spontaneously take on entering the Estate. It is generally flat and there are no challenging obstacles. As you would expect there are plentiful refreshment spots at the start and end of this circle.

The estate

The medieval ‘Barons of Stourton’ were the owners of this estate for 500 years. That is until, being staunch Catholics, they were dispossessed for supporting (and housing) Charles I during the civil war and so were forced to sell. Sir Henry Hoare (1677-1725) purchased it in 1717.

Hoare’s father had founded what is now the oldest surviving private bank in Britain, while Henry Hoare made his own very large fortune from the South Sea Bubble. Henry’s son (also ‘Henry’ (1705-1785)) developed the Palladian house and Arcadian garden between 1741 and 1750, perhaps echoing his Italian Grand Tour. This site would manifest for Hoare both refined taste and classical virtues. Maybe he was pursuing a style distinguishable from the contemporary but decadent Baroque of France. Hoare’s descendants then remained occupiers of this site until they gave it to the National Trust in 1946.

In brief, what Hoare did was damn the river Stour to create an artificial lake in the basin, around which he built a series of classical structures that are thought to imply (and invite) a mythical journey. This design is the ancestor of the sort of walk you might take today. It sets the scene for the kind of walking-in-nature later associated with the Romantic poets. Two particular scholars of this garden (Douglas Woodbridge and Ronald Paulson) have recently suggested what Hoare might have intended to achieve at Stourhead. They propose that the garden walk implies a journey that echoes Virgil’s poem the Aenead, in which Trojan hero, Aeneas, voyages around the Mediterranean towards Italy – where he then founds Rome.

If this is the case, then to experience the walk this way the modern visitor should proceed (as mapped here) in an anti-clockwise direction, encountering various motifs from classical antiquity until converging upon the Temple of Apollo – which functions as the Temple of Wisdom. Not all commentators are convinced that this is a credible ‘reading’ of the gardens – but, nevertheless, it is widely reproduced in guides. Certainly, Hoare knew well Claude Lorrain’s Landscape with Aeneas at Delos (1672) which does depict Aeneas standing in a Doric portico facing the Temple of Apollo, reflecting the Pantheon. Alternatively you can skip the classical allusions and just wander round – simply taking in the elegance and harmony of the constructed landscape.

Six stations on the walk

Most commentators write about the gardens as if they work at least to generate some sort of poetic resonance, whether Virgilian or not. In a sense they are a serious work of conventional art, but in the medium of landscape (“pretty as a picture” we say). The gardens are particularly celebrated for their apparent sensibility in relation to the English countryside. Gardening in that tradition suggests an idealised nature; plants are positioned as conversation pieces servicing a walk. Visually striking though it is, the picture book formality, with its closely manicured protection, may not appeal to all tastes.

There is a powerful intentionality in the design that may grate on some. For example, part of the existing village was incorporated with the gardens, simply to enhance further the romantic tone. Nevertheless, the structuring of big monuments in small spaces works to draw you towards them in turn and thereby creates an agreeable landscape walk. The landmarks of that anti-clockwise walk are summarised below according to map points above.

- Bristol Cross(pic 2) Formerly a market cross (1373, but much altered) in the centre of Bristol. The present Decorated Gothic piece replaced an Anglo-Saxon cross, commemorating the granting of a charter by Edward III to make Bristol a county. It got moved about a lot, as it increasingly got in Bristolians’ way. Until (in 1764) it ended up in this estate. Nothing to do with Virgil. And the Palladian bridge below doesn’t either – it is just a visual focus.

- Temple of Flora is dedicated to the Roman goddess of flowers and spring. Its welcoming inscription reads “Keep away, anyone profane, keep away” and so provides a salutary start to the walk.

- Grotto(pic 8) This comprises several passages and chambers, and statues of a sleeping nymph reclining above a spring of water (used as a Bath by Hoare) and also a river god. This place perhaps represents Aeneas’ descent into the underworld. Although dark in spirit, it does offer for inspiration a window with a view across to the Temple of Apollo. The steep path out of the grotto marks Aeneas’ difficult journey back to the upper regions.

- Gothic cottage This may once may have been a dwelling and may have had more to do with social life on the estate than with the Aeneid.

- The PantheonModelled on the same structure in Rome and originally called the ‘Temple of Hercules’ including a marble statue of Hercules. This could be where Aeneas sought an alliance with the Arcadians. Here he implored Apollo to “… grant us a home of our own. We are weary. Give us a walled city which shall endure, and a lineage of our blood”. It was renamed the Pantheon when statues including Diana, Flora, Isis and St Susanna were added in the 1760s. The Pantheon was regarded (and perhaps is still) as the most important visual feature of the gardens.

- Temple of Apollo (pic 10) Home to the Oracle of Delphi and the priestess Pythia, who was famed throughout the ancient world for divining the future and was consulted before all major undertakings.

The English Landscape Garden is one of the great English contributions to culture. Take it in at Stourhead! Come the late eighteenth century, gardens were no longer enclosed behind walls, walking was no longer an exercise on paths and indoor galleries, the natural world was no longer something frozen in a painting. This new landscaping of private land offered nature in multiple views and from this time landscape became something to be explored and contemplated for its own sake. (Incidentally, all this encouraged the English aristocracy to align their own identities with nature – pursuing country sports, being painted-in-landscapes and so on).

Finally, (or before setting out if you prefer), a visit to C14 St Peter’s church is worthwhile – the Hoare family pew is in the south transept.