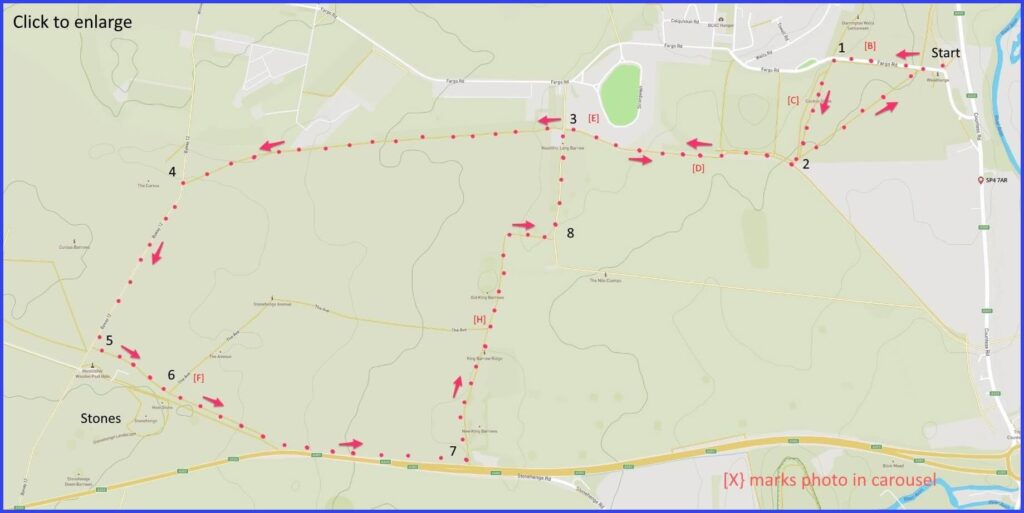

SP4 7AR An easy walk around Stonehenge. 5.5 mile, as shown – but cuts possible. Flat ground, few inclines. Old stones. (click map to enlarge. Click here for an aerial view) Click here to download/print PDF. (There is a GPX route option here for phone/tablet download. But only follow this link after watching this GPX help video). Friendly warning: all files relating to walks are published here on good faith but on the understanding that users must be responsible for their own safety and wellbeing.

(Routes from map points + metres to next point)

Start: Park around Woodhenge (view) [A] then walk forward towards bend on Fargo Road [B]. 380m

1: Enter field on left after “Larkhill” sign. Cross cuckoo stone field (view) [C] to a junction of footpaths. 400m

2: Turn right into a lightly wooded path [D]. Pass military domestic buildings to junction with lane.

3: Find an open field which you continue walking forward, following along its rightside wooded length. 1.3km

4: Turn left to lane (maybe with many travellor caravans), walking towards the stones. 800m

5: Enter the path just below the “ticket only” one. Admire Stonehenge. 400m

6: Follow path along fence. Becomes parallel with busy main road, until reach wooded perimeter. 1km

7: Turn left here and follow path alongside ancient barrows [H] then turning right and, shortly, left to walk forward with thick wooded area to your left. 1.5km

8: At map point 3, retrace to starting point. 1.5km

The pictures below are in the order things were seen on this walk. Clicking on any one will enlarge it (and the slideshow)

The walk

There is a car park in Durrington village adjacent to the Woodhenge. The landscape becomes quite bleak. While you will pass over land of great historical and cultural significance – that doesn’t promise immediate visual impact. The exception is your real destination – Stonehenge. Sadly, like film stars in real life, famous things are not quite as big as imagination expects (think Spinal Tap). But, to be fair, any sense of “seems small” needs to notice an effect of the vast open plain on which it stands (this drone video may help, perhaps best without the music). On these terms of scale, the henge can become a majestic sight and surely one to be seen by every Briton, once at least. By taking this long walk you do get a free sighting but also a calm one – compared to motoring up and dealing with the cost and brashness of the Visitors Centre.

Durrington

The walk starts in Durrington (or at least the general area of that village) which has been a settlement of some sort since neolithic times. Strange to think that this small and ordinary village was, in neolithic times, one of the largest settlements in north-west Europe. What its known for – to modern visitors – is little more than the place where you probably go to for starting a walk like this: namely, the site of Durrington Walls and the Woodhenge. The former are the traces of a familiar henge organisation comprising oval land surrounded by banked ditch. Folks lived here from about 2600 BC it seems: including, some suggest, the builders of Stonehenge. There is a further belief that the complementary structure of these walls represented for these people the ‘land of the living’ while Stonehenge and its burial mounds was ‘land of the dead’.

The second site at Durrington, Woodhenge, permits a little more visitor engagement [A]. Its a timber circle (i.e., not a stone one) originally comprising 6 concentric rings and a surrounding ditch. But the little blocks of wood are, of course, a simulation, not neolithic timber. They stand for things apparently much taller, and differentiated from each other in various ways. At the centre was found the burial of a crouched child with a split skull. Might be a sacrifice? Not certain because when remains were taken to London for examination they were accidentally destroyed during the Blitz. So might just be skull damaged by time. Another wood circle was recently found – now suggesting a complex pattern of monuments and avenues on this whole site. Mike Oldfield features it on one of his albums. But a more listenable tribute is this English Heritage video.

To Stonehenge

After taking in the Woodhenge you will pass (or perhaps sit on – [C]) the Cuckoo Stone. It’s a stone of the kind found at nearby Stonehenge. But it fell over. You will then be walking on the edge of Larkhill – Britain’s first military airfield (1909) and still visibly a hub for the large military presence on the plain. (The widespread rumour that they requested the stones be demolished (hazard to aircraft) seems to be untrue).

After a long walk across apparently dull fields (yes, a vacuous way to describe neolithic burial and ceremony sites) you reach a paved road that is likely to be well occupied by New Age Travellers – they have a long history of engagements at the site (such solstice gatherings were banned by Margaret Thatcher in 1985 – 520 arrests followed the inevitable protests). There is something both appealing and dispiriting about this community. Its easy to respect (admire even) their inventive disconnect from an unhappy world – while, at the same time, feeling just a bit uneasy about all the lay lines stuff. While taking the path through the very middle of this improvised settlement feels a bit unnerving, all is actually peaceful. Perhaps the danger is that their community will be undone by simply morphing into an accepted part of the Stonehenge brand.

When you reach the entrance for the Stones, because you probably don’t have a ticket you will take the footpath just below the official one (but the view is just fine). If you fancy a more mediated (and informative) view, try this video.

The route back involves some noisy walking near the notorious A303 single carriageway but eventually you turn right up the quiet pathway of the Kings Barrows [H]. Clear humps of land within which are ancient burials. The final part of this walk is a bit tedious – it has you revisiting where you set out and the area does not afford much by way of landscape views or even views of (less neolithic) Durrington village life. But then there is the shock of the henge: large craggy rocks in a gentle chalk upland landscape (the largest remaining area of chalk grassland in Europe). The Bluestones came from the Preseli mountains in Wales, the large Sarsen stones from the Marlborough Downs up the road. It isn’t so much the transport that was a challenge (probably took a year from Wales) but the dressing or pounding flat of the stone surfaces.

For a long time all this was privately owned. Henry VIII launched its privatisation after dissolving Amesbury Abbey. Sir Cecil Chubb (1876-1934) was the last private owner. He impulsively paid £6,600 at auction in 1915 (£0.5m today) to buy a present for his wife (paid for with his wife’s inherited money). Fortunately, he later gave it to the government in 1918 (his wife was not impressed with the gift). There were terms however. Public access was to be encouraged, but should be “on the payment of such reasonable sum per head not exceeding one shilling” (currently inflated to £19.50 admission).

Stonehenge has had its imitations (e.g. Foamhenge) but do get to visit this Wiltshire site for the real thing in neolithic experience. In which event, considering Stonehenge as a walk is strongly recommended – over rolling up to the visitors centre. Perhaps the walk revives some distant cultural memory of pilgrimage or ritual. Its a striking sight as you approach it. And even rather unsettling when you are up close.

![[A]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/01-150x150.jpg)

![[B]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/02-150x150.jpg)

![[C]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/03-150x150.jpg)

![[D]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/04-150x150.jpg)

![[E]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/05-150x150.jpg)

![[F]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/06-150x150.jpg)

![[G]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/07-150x150.jpg)

![[H]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/08-150x150.jpg)