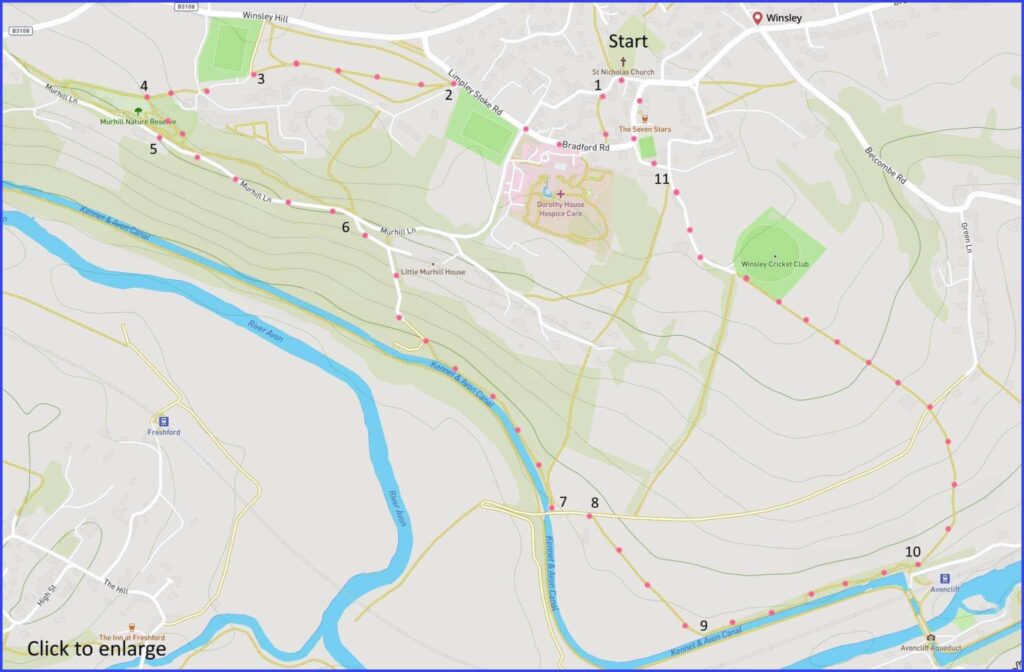

Click map to enlarge. Very pleasant 4-mile walk from village, along canal and return. Some steep walking and wooded paths. Final part of twopath is marked but narrow. Short cut at point 7 on map. Parking possible close to church. Click here for arial view. Click here for printable PDF download. (There is a GPX route option here for phone/tablet download. But only follow this link after watching this GPX help video). Friendly warning: all files relating to walks are published here in good faith but on the understanding that users must be responsible for their own safety and wellbeing.

(Route from map points + metres to next point)

From Start, turn right at the church gate, walking towards house on the corner. 25m

1: Veer left down the path here until you meet Bradford Road. Head right, past Dorothy House on left until marked footpaths at Quarry Close. 390m

2: Take the middle of three routes, follow centrally and towards left of field where path enters a short wooded section. 300m

3: Walk across an open parking space (for adjacent housing). 90m

4: Take ‘permissive footpath’ down the field. Through gate and follow path downwards (steep) towards road, looking for a road entry point (found towards right here). 120m

5: Follow this lane to Muirhill junction. 320m

6: Forward and right, down very steep lane (bear right at Muirhill house gate), it becomes a path and ends on canal towpath. Follow canal to the left. 660m

7: At bridge, take steps to lane and head left. 70m

8: (Walk forward for a shortcut avoiding rather overgrown towpath), otherwise take steps on right to directly cross field. 270m

9: Take stile to enter towpath (marked but more hazardous). 430m

10: At the aqueduct take the path upwards. At lane crossing, take shaded path to left of 6-bar gate. Continue past cricket club. 765m

11: Turn left past the village hall and pass (or visit) Seven Stars pub on way to start point. 240m

The pictures below are in the order things were seen on this walk. Clicking on any one will enlarge it (and the slideshow)

The Walk

Winsley: a dormitory village for Bath. Add a significant number of retired people and, during the daytime, the village becomes a quiet place to start a walk. Begin this one at the parish church. It’s a Victorian rebuild (1841) of an older foundation. The interior is not exceptional: it has a ‘village hall’ feel to it (although admire the colourful kneelers). However, the 16th century church tower (with saddleback roof) has been retained: it is quirkily attached to the main building by an arch (no through traffic). From the church, walk along a typical part of the old village – passing on the left Winsley House (17th century origins), now a Dorothy House hospice.

The main walk then passes down the very agreeable Murhill Bank – a limestone meadow purchased by the Parish Council and managed by them since 1987. This is land that has never been ploughed or sprayed and so it is a rich spot for flora and fauna. The quarry hillside is steep, and the path is tricky under foot in places. But quite manageable. It drops onto Murhill Lane at various points (select one) which then leads down to the canal. There, a winding towpath leads to the delight of the Avoncliff Aqueduct. (Or is it Avoncliffe?) This, along with the nearby Dundas Aqueduct, carries the Kennet and Avon canal over river and railway. The final part of the walk is a steep field path – upon which, very sadly, cattle from the adjacent field once caused fatal injuries to a walker. No problems now: it’s well fenced.

The uphill route leads back to the village. It passes Winsley’s bowls and cricket clubs (the village excels in both), then a village hall and, finally, the Seven Stars pub – strongly recommended for refreshment.

Winsley: stone

There is much about Winsley that is picturesque. And yet this village was once alive with a heavy industry. Although in this case the picturesque and the industrial are closely linked. Because – to put this in very general terms – a local history can often be detected, as here, in the vernacular architecture of a place. That visual record can express the crafts and the materials that have been central to community life. In Winsley’s case it is the freestone quarried at the Murhill Bank hillside that is visible today in village dwellings. The idea of such links between local building materials and local history is explored well in this Cotswolds case study.

While the buildings of Winsley display its quarrying history, the quiet charm of Murhill bank rather conceals it. Because it was on this so-peaceful hillside that the quarries (and their engineering) were once located.

Winsley’s current prosperity has grown from the labour of those 18th and 19th century quarrymen who worked the hillside stone at Murhill. (A good sense of that labour is conveyed in David Pollard’s book ‘Digging Bath Stone’.) On walking down the hillside there are plenty of indications of an industrial past. Including a quarry entrance around point 6 on the map. While here and there are even signs of the tramway lines that took stone to the canal wharf at the bottom of the present slope. This map sketches the quarrying area. And this video exploration gets up closer to the details of what is still visible underground around here.

Winsley: canal

The Kennet and Avon canal allowed quarries such as Winsley to compete with the London Portland quarries, and many others. Stone was passed down to the canal wharf on tramways and then exported around the country. This 87-mile canal was built in order to connect the Bristol Avon with the Thames at Reading. The so-called ‘golden age’ of such canals and their traffic ran for about 50 years up until the 1830s. At that point the coming of the railways created tough competition for canals as a mode of transport – ironically, stone from Winsley was used to build Temple Meads station in Bristol.

Winsley stone was also used to build the Avoncliff aqueduct that forms a turning point on the present walk. The traffic on and around that structure is a good reminder of how the English canal system was rescued for recreation, with the decline of its industrial role. Such leisure development owes much to Tom Rolt’s example in his 1944 book ‘Narrow Boat‘. But also to vocal celebrity enthusiasts such as Prunella Scales and Timothy West. The boats’ spaces for cargo-carrying have given way to covered areas that are living quarters. Originally, boatmen and their families lived ashore, not on their boats. Although as competition from the railways increased it seems some of them did use the boats as homes, not least because family members could share the hard work.

Such a troubled past is hardly visible in the gentle flow of current canal traffic. The Avoncliff aqueduct is one particularly grand, but agreeable, place to witness it.

![[A]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/winsley_01-150x150.jpg)

![[B]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/winsley_02-150x150.jpg)

![[C]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/winsley_03-150x150.jpg)

![[D]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/winsley_04-150x150.jpg)

![[E]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/winsley_05-150x150.jpg)

![[F]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/winsley_06-150x150.jpg)

![[G]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/winsley_07-150x150.jpg)

![[H]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/winsley_08-150x150.jpg)

![[I]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/winsley_09-150x150.jpg)

![[J]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/winsley_10-150x150.jpg)