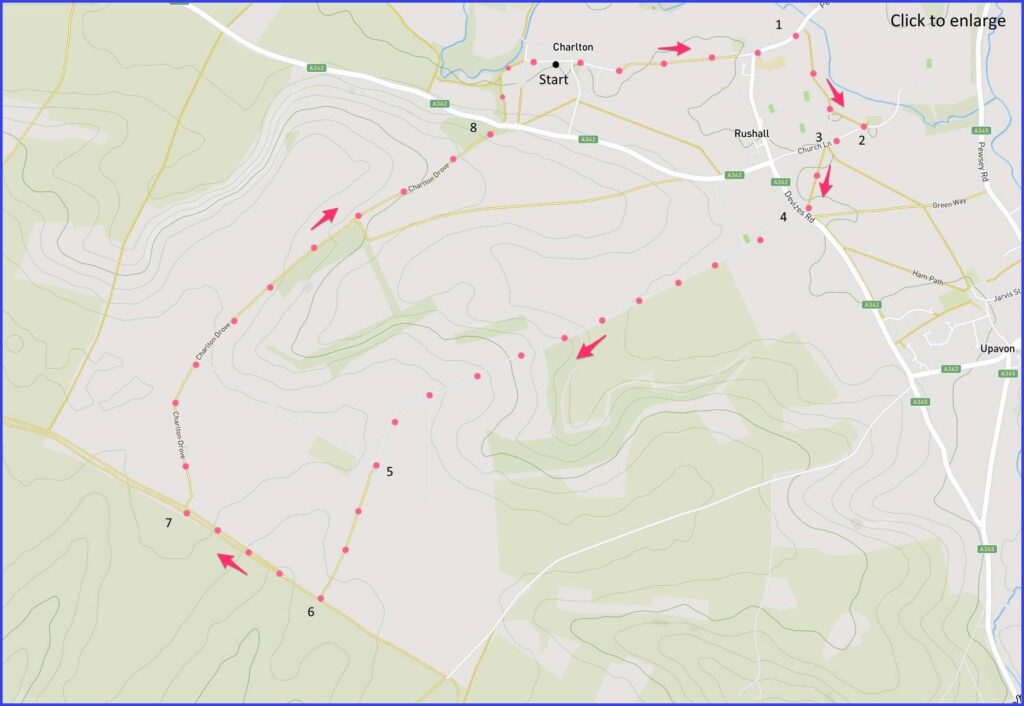

(Routes suggested from each map point + metres to next point)

From start point walk forward. Cross Devizes Road at junction with row of brick houses. Walk to footpath on right of slated fence. 950m

1: Through gate. Cross field, walk parallel to river and row of three trees. Head for the church and gate to road. 420m

2: Turn right out of church. Walk to marked path and kissing gate on right. 70m

3: Walk diagonally across cricket pitch to gate in middle of fence. Walk diagonally to road. 250m

4: Walk paved lane of Rushall Drove [D] until passing left-leading path (now private) [E]. 2km

5: Continue straight to intersection with military road. 550m

6: Walk up this track to Charlton Drove entrance on right [H]. 770m

7: Walk this path [I] until junction with main road. 2km

8: Take steps down to footpath adjacent to Charlton Cat turning right to start. 400m

The pictures below are in the order things were seen on this walk. Clicking on any one will enlarge it (and the slideshow)

The walk

Charlton St Peter is served by such narrow lanes that it almost seems to be defying visitors. However, there is some (tight) parking on Friday Lane west of the church. Otherwise, an alternative plan is to start the route with verge parking near Rushall church (point 3 on the map). Then take either direction for the walking, according to preference.

These two villages provide a pleasing start to a short, but invigorating, walk. Two particular moments promise to be highlights. First, if you do take the walk routed here, then the sight of Rushall church – and the slow approach towards it – is something special. Second, there is your experience of walking the panoramic Pewsey/Salisbury landscape. If you appreciate a wide-open, wind-swept, walking experience with to-the-horizon views [G], then the drover paths on this route are a treat. Well, yes, perhaps for some purists the encounter is quite brief on the expected scale of such things. Brief but still bracing. Anyone wanting to make it a bit shorter might be tempted by the apparent cut across at point 5 [E] that is visible on the above map. Sadly, this is one of several routes that Rushall Organics (see below) seems to have rendered private.

Warning to lovers of the pastoral walking experience: the drover lanes taken on this walk are also favourite routes for off-roaders. In particular, the Charlton Drove is – understandably perhaps – a magical route for this hobby. But it is still a very tiresome intrusion on the walker’s peace. However, live and let live. Just keep your ears open – not just your eyes.

Walking is for both mind and muscle. Exercise the imagination on this walk with some of the themes below

‘St Peter’ – why and how?

Place name authorities say that ‘Charlton’ is from the Old English ceorla-tun, meaning ‘settlement of the lord’s ceorlas’. Where a ceorla (or ‘churl’) was a peasant or ‘person of no rank’. So it’s no surprise that around the UK there are 17 ‘Charltons’ (three of them in Wiltshire) – unsurprising, because in the past there must have been many persons ‘of-no-rank’ seeking different places to settle.

The case of Charlton makes one think more generally about this multiple naming. In the UK there are 55,000 different ‘places’ (cities, towns, villages, or hamlets for dwelling). A reasonable question is: Just how many confusing Charlton-like name duplicates exist more widely across the country? I can’t find the answer. But ‘Charlton’ provides some insights regarding historic solutions to the duplicates problem, if not to its scale.

At some point in the past, certain Charlton ‘churl-settlements’ must have differentiated themselves by appending their core name with a bit of geography. So, we find Charlton on the hill and Charlton-on-Otmoor and Charlton Riverside. You can probably think of more prominent examples. If you can’t, then what about Bradford on Avon or Newcastle-Under-Lyme? Although these cases create their own kind of confusion. For example, definitely don’t say ‘Bradford Upon Avon’ in Wiltshire. And what about the hyphens – do we use them or not? An alternative place-differentiating strategy is to anchor a core name to the local church. So we have Charlton All Saints. And, of course, we have Charlton St Peter.

The example of appending ‘St Peter’ to a ‘Charlton’ then has to be adopted. A reasonable guess is that such a change passes only slowly through the ‘system’. For it may require multiple levels of approval. For instance, the change has certainly been adopted for road signs. But, on the other hand, wiltshire.gov don’t seem to use the ‘St Peter’ part. They say “Charlton (Vale of Pewsey)” (to distinguish it from “Charlton (North Wilts))”.

People have their reasons for making place name changes – and those reasons are various. For instance, animal rights groups recently proposed that ‘Wool’ (a village in Dorset) should change its name to ‘Vegan Wool’ (whither ‘Ham’ and ‘Cheddar Gorge’?). Yet the process for changing a placename can’t be easy. Surely there are a lot of individuals and agencies that have to go along with it? Some sources claim that Charlton became ‘Charlton St Peter’ in 2003 (to regularise postal and delivery mis-directions). Current road signs and ordnance survey mapping might imply that a petition to make the change was successful. If so, then why does wiltshire.gov not reliably use it (see above) and how could a proposed change arise on the agenda of Wiltshire Council in 2022 – as if it was a fresh idea?

That agenda document hints at the process involved. Specifically, such a change may be progressed “under s.75 of the Local Government Act 1972 at request of the relevant Parish Council”. There is supposed to be a survey of inhabitants to support the petition. In the case of Charlton it seems that no one replied. But this may not matter, because the change can still be adopted at Council discretion – if it is thought that “reasonable grounds” exist. In the present case, the change proposer had submitted that: “The reason for the suggestion is that this is the name widely used for Charlton and by which the parish is recognised, and how the parish council is referred to at present.” Sort of: “its happened anyway, so lets go with it”. This worked. Although hopefully there is a ‘name change officer’ who can spread this news and make the name stick in the depths of local government administration.

Charlton St Peter: A place

Wiltshire settlements of this sort tend to have a common core of features. Typically: a church, a manor house, a pub and a phone box. There may also be a village shop (but not here) and thatched houses (yes, many here).

The phone box works, but the pub (Charlton Cat) – a 1750s alehouse – has become a tea room (pleasant). The village church [A] has also undergone some re-invention. While there is various evidence of a church here since the 12th century, what we see today is largely Victorian. Although it does boast its age by incorporating a 16th century side chapel – funded by the legacy of one William Chaucey. (How so much fine church building arose from a funder’s faith in salvation. What is the modern equivalent? An art gallery wing at least memoralises.) Then there is the manor house: it is at the western end of Friday Lane. An 18th century foundation (but little survives from that period). Today the manor hosts a caravan and motorhome club (how do they negotiate the lanes?).

Whatever its present identity, historically ‘Charlton (Vale of Pewsey)’ was a quite ordinary Wiltshire community based on farming. But Charlton is actually quite well known beyond Wiltshire. This is because of one particular individual who was born into that community. The village’s discreet claim to fame resides in the reputation of a local farm labourer named Stephen Duck (1705-1756). His is a rather extraordinary story.

Duck’s tale

That a humble thresher lad can start life in rural Wiltshire (this very place) and proceed to become the toast of literary London is not a story that is easy to make sense of. It presents a rather sobering case study for unsettling certain simple ideas about human talent and where it comes from. Perhaps the case seems surprising because it questions our beliefs that such talent is a family inheritance. If this inheritance is ‘in the genes’ then that seems to upset the prejudice that a farming village furnishes an unlikely gene pool. While, on the other hand, if we believe (more enlightened perhaps) that talent is inherited via the family environment supporting an individual’s growing up …. then a simple farming village may still seem an unlikely starting point for Duck’s extraordinary trajectory. But, oddly, neither explanation embraces the phenomenon of the auto-didact. Neither centres on the agency of the individual – being responsible for their own development. Striking though this story is, it is worth noticing that it is not unique. Consider the very similar case of the humble Bristol poet – Thomas Chatterton.

Although Duck left school at 14, he displayed an unusual thirst for knowledge. (Does this kind of commitment have a trigger point? What might a trigger point be?). A necessary (but certainly not sufficient) basis for a journey of intellectual development would have been learning to read at school. Having got that in place, Duck – along with a friend – set about satisfying this thirst through collecting books. The couple built their personal library and they studied together. First arithmetic, but then literature and poetry. Eventually Stephen himself started writing and, in fairytale fashion, he was ‘discovered’ by a local parson (the Rector of Pewsey). His poems were propagated through a sympathetic aristocracy and, eventually, they reached Caroline, the Queen Consort of George II (Stephen later married her housekeeper). Greatly impressed, Queen Caroline set him up with an annual salary and, later, various employments. His final position was as Rector of Byfleet after Caroline’s death (and so the death of her patronage).

Stephen Duck published several collections of poetry: these built a reputation whereby he became widely known as the “thresher poet” (see examples of his work online here, listen to scholarly discussion of it here). Sadly, in an apparent fit of depression, he ultimately committed suicide. By drowning. To be fair, some authorities are a little uncertain about this ending – although others are so precise as to say it was “in the trout stream behind the Black Lion at Reading”.

It is surely natural to expect that a village would memorialise such a celebrity. With this in mind, you may notice a ‘Duck’s Cottage’ sign at the end of Friday Lane. Don’t be seduced. This dwelling, once a stable block to the local Manor House, is hardly convincing as the implied home of a local thresher. Although the name may work well for a Wiltshire holiday let. More authentically ‘Duckian’ is a ‘Duck’s Feast’ at the Charlton Cat. In 1729 one of the poet’s patrons (Lord Palmerston – Wiltshire landowner and great grandfather of the prime minister) left in his will funds for an annual celebration event that would be open to 12 local threshers. It seems to have remained a tradition regularly held on June 1st. But don’t try to attend. At least not unless you are one of the specified dozen married men who have lived in the village for a number of years and worked on the land (surely a big ask these days?). Ah, there is also a thirteenth chap – the ‘Chief Duck’ – who, yes, wears some sort of crazy hat.

Rushall: villages and village churches

Probably there are no eminent poets associated with neighbouring Rushall. Although celebrities have passed through. When the ‘Rushall Horse Trials’ were flourishing, the village welcomed some fairly distinguished visitors of a more horsey variety. However, all the traditional village features are here: certainly a fine parish church and way back in time there was a notable manor house. Not that the church you see today is that which stood here in the Norman period. While the present church building does have roots back to 1332, its attractive brick, stone and flint build is more early Victorian. Nevertheless, it does have a few remnants of the 14th century (such as the font). But surely most striking are the two 15th century stained glass windows in the south chancel.

The Rushall church [B] lies in a romantic isolation. Charming, but also puzzling. Your typical parish church lies most naturally at the centre of a medieval village community. How can this one be so firmly detached? This oddity is explained in the history of Rushall’s former manor house. There was a manor house here in 1332; at that time the present church was located close to this house. Later, in the 18th century, a new manor house was established (perhaps incorporating parts of the old) by Sir Edward Poore. This wealthy MP (for Salisbury) bought up most of the parish of Rushall and altered the village layout to suit the extensive grounds of his house. The existing church thereby became a ‘feature’ within those grounds. And thus it became detached from the village. Around 1839 the Poore manor house was demolished, seemingly as a consequence of the land being split up among heirs and then sold off piecemeal. The church of course stood. Untouched but now isolated.

The Poore family association helps explain one other local curiosity – the name of the Charlton Cat. In the 1820s this pub was called the ‘Poore Arms’. Outside the Inn was a version of the Poore Baronetcy coat of arms. It is said that its design included a pair of badly painted leopards. On that basis the pub become known locally as “The Cat”. And – as these things often go – an affectionate title percolated up to become official. Perhaps like the ‘St Peter’ and Charlton (Pewsey).

Rushall seems home to a thriving community – at least as projected by its local website. As a working village, its identity is currently dominated by Rushall Organics. This is a farming business that has built a reputation based on the chemical-free cultivation of wheat. By all reports, excellent bread results from this and it is sold locally (somewhere, but see if you can find it). The company’s “brand story” is set out here.

By the way, there are three more Rushalls in England (this one is the best)

![[A]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/charlton_01x-150x150.jpg)

![[B]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/charlton_02x-150x150.jpg)

![[C]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/charlton_03x-150x150.jpg)

![[D]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/charlton_04x-150x150.jpg)

![[E]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/charlton_05x-150x150.jpg)

![[F]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/charlton_06x-150x150.jpg)

![[G]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/charlton_07x-150x150.jpg)

![[H]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/charlton_08x-150x150.jpg)

![[I]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/charlton_09x-150x150.jpg)