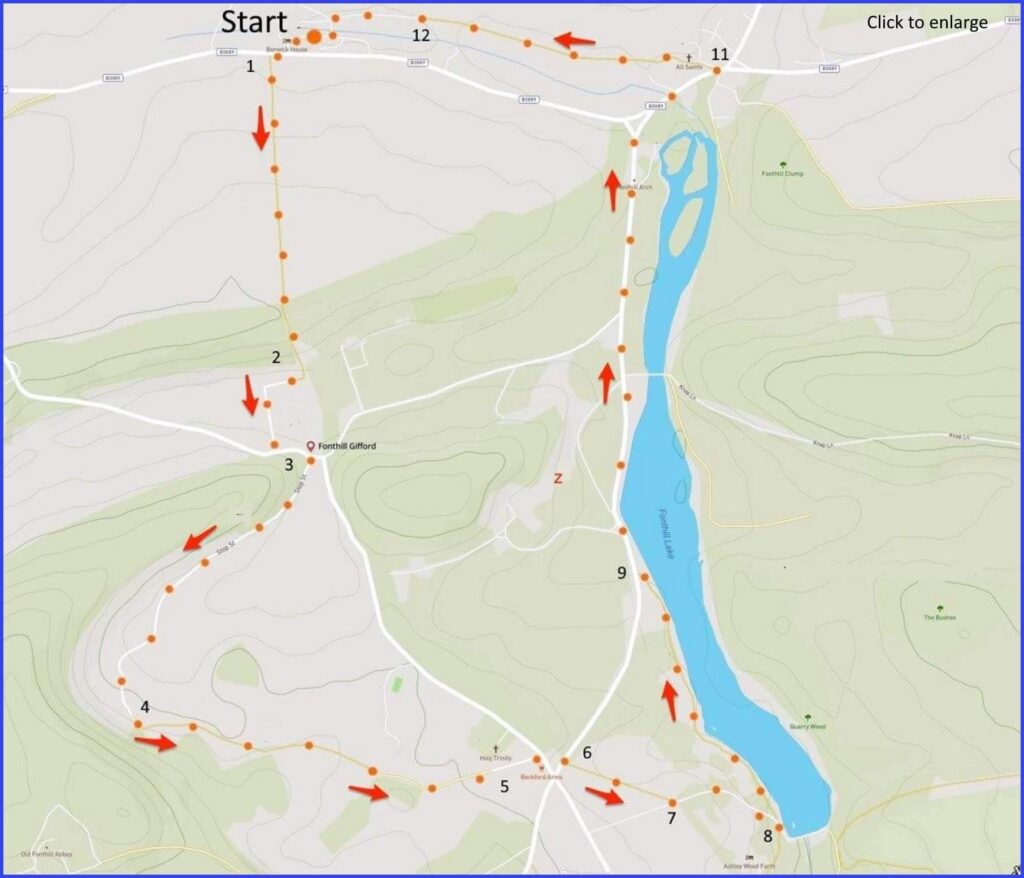

SP3 5UA 5-mile walk around Fonthill Gifford on lanes and fields and alongside a lake. Some fine churches on the way. No stiles. Click map to enlarge. ([fo] is popup footnote.) Click here for an aerial view. Click here to download/print PDF. (There is a GPX route option here for phone/tablet download. But only follow this link after watching this GPX help video). Friendly warning: all files relating to walks are published here in good faith but on the understanding that users must be responsible for their own safety and wellbeing. There is also a walk outline on YouTube.

(Route from map points + metres to next point)

Start: Head for Berwick St Leonard. Not quite a village: more a small business estate. Road entrances suggest private – but not so. Parking possible. Walk towards exit of village and to main road via 3-storey apartments house. 250m

1 : Head right past bus stop, cross road to footpath. Enter path and shortly take gate on left to walk up left side of field. It becomes a wooded area. Continue on wooded area. Short steep slope down! Walk through this to lane path. 850m

2 Follow L-shaped lane past house to junction with Stops Hill. At this junction, turn right until junction with Stop Street on right. 150m

3 Follow Stop Street until it turns into a footpath. 860m

4 Join this field path, first across field, then following a line of trees, then open path towards Wood Lane. 1km

5 Follow straight line across several fields towards the church spire here. Pass Beckford Arms, Cross to left/up road for this field gate on right. 230m

6 Walk across field path to join lane. 300m

7 Turn left on lane and follow to base of lake and dam. 400m

8 Ignore dam but take field path entrance to left. That path shortly starts to follow the near side of lake. Walk forward until reaching a parking layby on left and chance to join road. 750m

9 Join this road at the layby (although rough path does continue alongside lake) and head towards gates and beyond to road junction. Take right fork towards church on left. 1.1km

11 Walk through churchyard and onward on fieldpath towards Berwick village. 690m

12 Lane then rejoins Berwick St Leonard and start point. 300m

The pictures below are in the order things were seen on this walk. Clicking on any one will enlarge it (and the slideshow)

Pevsner comments: “The story is of lost great houses in a landscape of great beauty”. Or to put history less kindly: a story of the very wealthy seeking an aristocratic identity for their families through an extravagance of architecture, furniture, and landscape. However, Pevsner supplies the key word: “lost”. The grand buildings and their paraphernalia have all gone (or are concealed), although their story has been well chronicled. In short, while the buildings are widely referenced in guide books, not much of that is visible today. So the walking could be considered to be through a landscape ‘skeleton’ of history. But it nevertheless remains a very memorable visual experience. (If your appetite is stimulated – try Caroline Daker’s book Fonthill Recovered for the full history of the estate.

The walk

The start point of Berwick St Leonard may once have had the look of a Wiltshire village, but now – apart from a farm – it seems to be a small business park owned by the Fonthill estate. Don’t be put off stopping there: it’s still a public place. Although even its C12th St Leonards church ([A] rebuilt 1860, and probablly open) is a “redundant church” (now more comfortably termed “closed church” by CofE).

The area was Intensely occupied in Roman times. But its medieval history is largely a succession of three families – and their servants, craftspeople, and farm workers. Little remains of that period. Most domestic life today is concentrated on Stop Lane (note some interesting old semi-detached cottages). There is a small village hall half way up but, otherwise, the outside world is just a mailbox at the end of the lane (collection 5 pm).

Stop Lane heads to Fonthill Gifford, which is mainly the mini-cathedral of Holy Trinity church (see [G] but its likely to be closed weekdays). Not as old as it looks (1866) but rebuilt on the site of a much older church. For less spiritual sustenance there is the Beckford Arms – a classy pub with good ales, spacious dining, and a luxuriant garden. From here head up the lake (it’s dammed at the south), admiring the wild swans perhaps [H] (and avoiding more eccentric flying creatures). Notice the C13th church of All Saints on the path back [J].

Beckford Fonthill

The estate has a long history. In the ‘Beckford period’ (1744-1822), it became famous for the magnificence of its buildings. It is still a site of English aristocracy. But its greatest days remain a period defined by the evolving estate architecture of the Beckford family.

First there was Alderman William Beckford (d. 1770) MP for Shaftesbury and twice Lord Mayor of London. This was a man of vast wealth (“the richest commoner in England”) – but wealth taken from Jamaican plantations, where he owned 3000 African slaves. He purchased the Fonthill house and the 5000-acre deer park estate from the Cottington dynasty in 1744. The house was destroyed by fire in 1755 so Beckford rebuilt it as the “palace” of Fonthill Splendens – on the same site which is roughly where the cricket pitch is today, just west of the Lake path. That lake arose from Beckford damming the stream that feeds into the River Sem at Tisbury. He planted many trees and added the archway (Inigo Jones?) still standing at the head of the road to ensure a grand entrance.

William Thomas Beckford (“the younger”, d. 1844) was an art collector, writer and musician (it is even claimed he had some lessons from Mozart). He hated the country sporting pursuits of his class but he inherited his father’s estate (at nine years) along with his father’s fortune – because among many offspring he was the only legitimate one (a child of “very delicate and tender constitution”). Beckford Junior lived in Splendens for 30 years before having it demolished. While he spent long periods overseas – to avoid the possible legal consequences of certain scandalous habits – much of his work when present on the estate took place during 1796-1813. At that time he conceived the oversized Gothic folly ‘Fonthill Abbey’ (explanatory video lecture here). It has no right to be termed “Abbey” – that name was Beckford’s whimsy. Some of this building borrowed from the sadly demolished parts of Splendens. The abbey’s main tower (an extraordinary 280 feet) collapsed several times: doing so finally in 1825. So there is little left to see (unless approached through virtual reality). In the route map included here it is labelled ‘Old Fonthill Abbey’ (but not easily accessible).

When Beckford Junior moved to Bath (cf. his Beckford Tower there – another folly), the remnants of Splendens briefly became an Inn, while a woollen mill was constructed at the end of lake. All this industry failed, until the land was sold in 1829 to millionaire draper James Morrison. His grandson, Hugh Morrison, built on the estate east of the lake (1904). Although this was later demolished and made into Fonthill House in 1972 by Hugh’s son, the Conservative politician and peer John Morrison – otherwise Baron Margadale of Islay. Morrison had gained the very last hereditary English peerage to be created (motto: “Prudence before any thought of reward”).

Modern Fonthill

The Morrison Baronetcy own a large proportion of Islay in Scotland (73,000 acres). This probably explains how one craft to be imported to the estate is whisky distilling. Yet perhaps such small businesses can gracefully populate the modern Fonthill landscape. As to the house, the website declares “The gardens are a haven for the 3rd Lord Margadale of Islay and his family.” Sadly, the haven is only open to others on about three days in the year.

The notorious Beckford Junior was somewhat reclusive, but he was also said to enjoy the excitement of social gatherings. When the Honourable Nancy Morrison [fo] recently threw a lavish party on the family’s 9000-acre estate, locals for miles around were kept awake until 8 am. Residents observed that they might risk being seen as modern Serfs. Many traditions remain protected here.

![[A]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fontillA-150x150.jpg)

![[B]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fonthillB-150x150.jpg)

![[C]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fonthillC-150x150.jpg)

![[D]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fonthillD-150x150.jpg)

![[E]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fonthillE-150x150.jpg)

![[F]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fonthillF-150x150.jpg)

![[G]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fonthillG-150x150.jpg)

![[H]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fonthillH-150x150.jpg)

![[I]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fonthillI-150x150.jpg)

![[J]](https://wiltshirewalks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fonthillJ-150x150.jpg)